“I knew I wanted to paint very early on – painting was my secret garden. My art was an escape out of Heterosoc, and for me to use the word ‘queer’ is a liberation; it was a word that frightened me, but no longer.”

— Derek Jarman

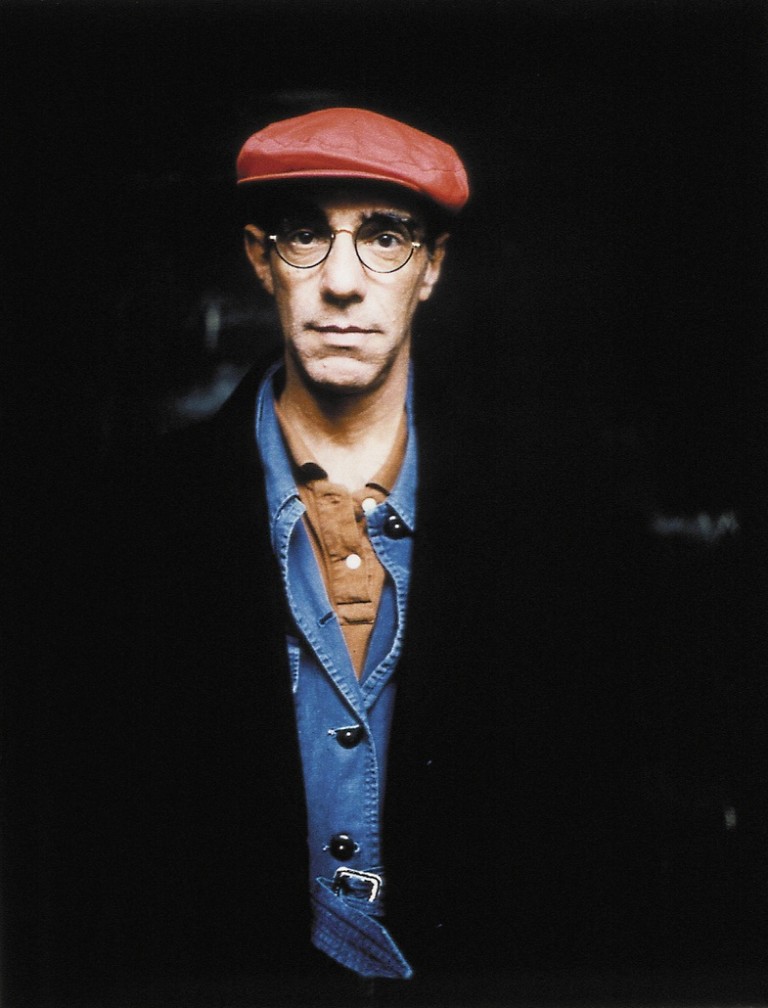

Derek Jarman | Image courtesy of the artist and the British Film Institute

Born in 1942 in Northwood, Middlesex, England, Derek Jarman was one of Britain’s boldest directors. Although principally known for his films including Sebastiane(1976), Jubilee (1978), Caravaggio (1986), The Garden (1990), Edward II (1991), Wittgenstein (1993) and Blue (1994), Jarman was also a keen painter and poet, writer and memoirist, gardener and activist.

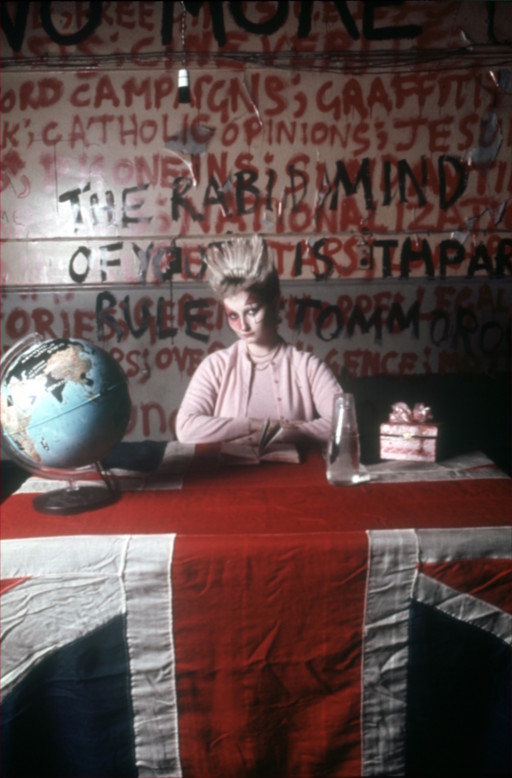

Film still from Derek Jarman, Jubilee, 1978 | Image courtesy of the artist and the British Film Institute

In the 1950s, Jarman first began to paint seriously at boarding school. As his father insisted that first he complete a ‘proper’ university degree before studying fine art, hecommenced a BA in History, English and History of Art at King’s College London in 1960 after leaving the boarding school. Jarman first became known as a stage designer. Before moving into costume and set design for the Royal Ballet, Ballet Rambert and English National Opera in 1967, Jarman studied painting and stage design at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London from 1963 to 1967.

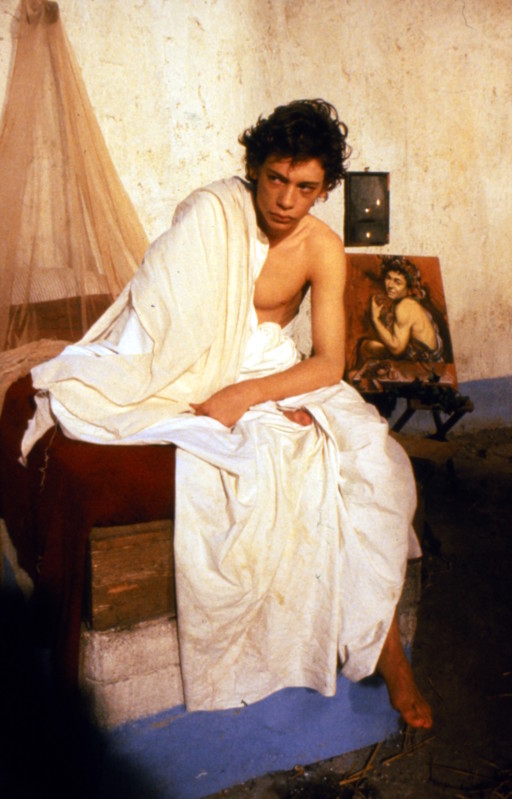

Film still from Derek Jarman, Caravaggio, 1986 | Image courtesy of the artist and the British Film Institute

During his time at University College London, Jarman took a course on world cinema and a few years later began experimenting with making his own films in the low budget ‘Super 8’ format. His break in the film industry came as film designer for Ken Russell on The Devils (1971) in 1968. In 1971, he directed his first full-length feature film, Sebastiane (1976), one of earliest British films to include positive images of sex and intimacy between men.

Derek Jarman participating in the OutRage! March at Parliament | Image courtesy of Peter Tatchell

In the early 1970s, Jarman was a committed and vocal campaigner for LGBT rights, involving himself heavily with gay liberation groups including the Gay Liberation Front and OutRage!. He was the first UK public figure who opened about his HIV status and discussed his condition in public. In 1986, he was diagnosed as HIV positive. As one of the keynote speakers in the world’s first ever AIDS and Human Rights conference in 1988, Jarman gave a speech about his own HIV status and the need for governments to switch the focus from repression to education, support and treatment. During the 1980s, Jarman was a leading campaigner against Section 28 of the Local Government Act, introduced into British law in 1988, which sought to ban the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools. In 1994, Jarman died of an AIDS-related illness at the age of 52.

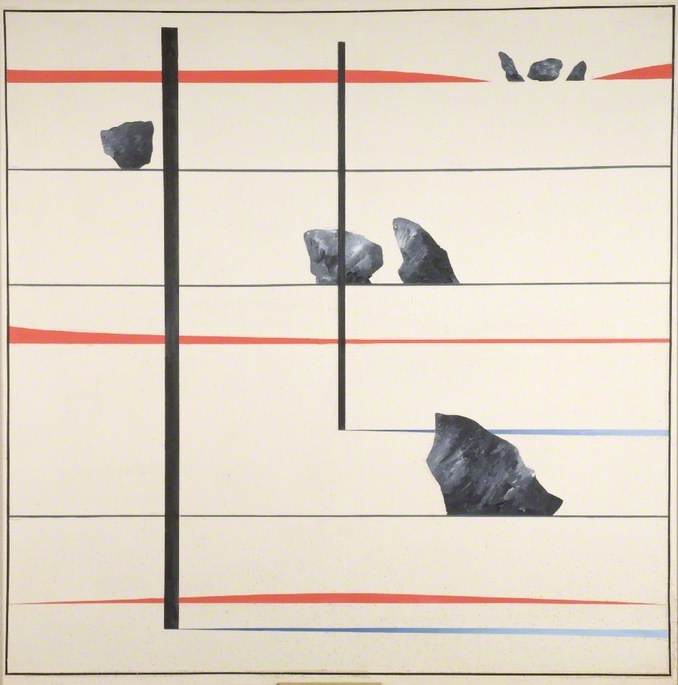

Derek Jarman, Avebury Series No. 4, 1973 | Image courtesy of the artist and Northampton Museums & Art Gallery

Painting — Jarman’s earliest artistic passion and returned to his last decade

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Jarman’s paintings tended not to reference his sexuality overtly but focused on the nature and experience of landscape. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, his late paintings conveyed a palpable sense of anger but also laced with humour and defiance, such as works in the ‘Queer’ and ‘Evil Queen’ series were informed by Jarman’s involvement in HIV/AIDS activism. ‘Queer’ features Jarman played a central role in reclaiming the term ‘queer’, offering a possible alternative to rigid labels and categories of sexual and gender identity.

Derek Jarman, Queer, 1992 | Image courtesy of the artist and Manchester Art Gallery

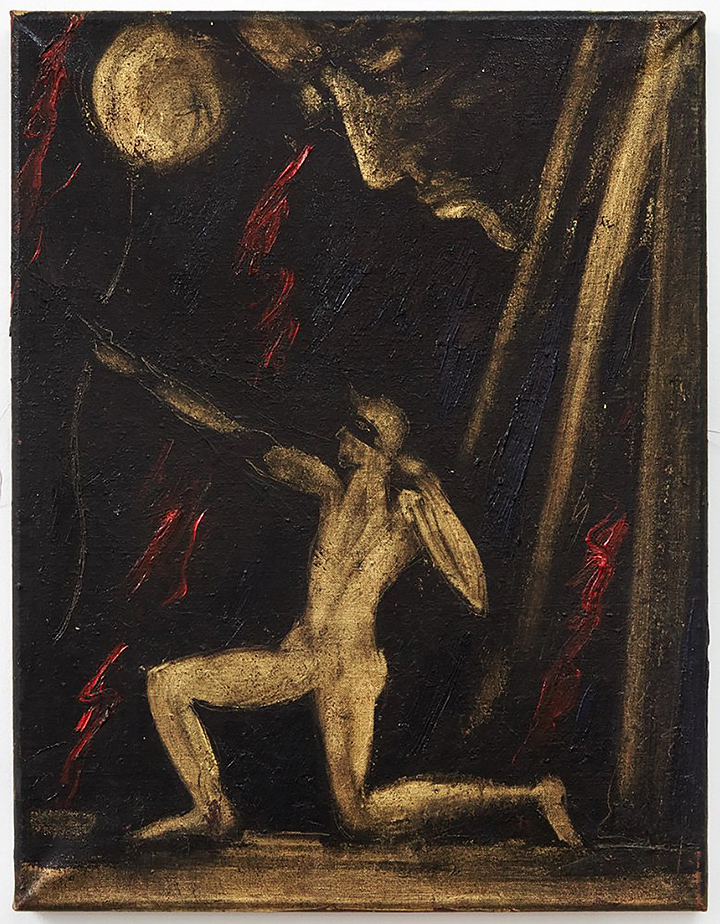

Before pre and post–dates Jarman’s diagnosis of HIV, his work became blacker and blacker. Jarman wrote in Chroma: A book of Color, ‘moths which turn black to hide from predators… I painted the gold into my black paintings (melanosis)’. Jarman referred to ‘melanosis’ – the phenomenon where moths evolved to a darker color to blend with the soot of the industrial revolution and avoid predators. He made sure there was a contrasting brightness that illuminated his messages from the tarry black background, itself a metaphor for dark waters and shadowy corners where enemies lay in wait.

Derek Jarman, Untitled (Archer), 1983 | Image courtesy of the artist and Sunpride Foundation

Jarman’s Prospect Cottage and garden

After being diagnosed with HIV, Jarman got as much out of life as possible and started creating a garden. Next to the nuclear power station at Dungeness on the Kent coast, he made a Prospect Cottage without boundaries that combined plants with sculptures made of found objects such as stones, driftwood and the debris of old fishing boats.

Derek Jarman in the garden in front of Prospect Cottage | Image courtesy of the artist and The Art Fund

During his time there, his creative outpouring was immense, from flotsam and jetsam sculptures to paintings of red scratchings and black tar. Jarman also used the garden and surrounding landscape for scenes in his films The Last of England (1987) and The Garden (1990).

Derek Jarman, Landscape, 1991 | Image courtesy of the artist and Sunpride Foundation

Film still from Derek Jarman, The Garden, 1990 | Image courtesy of the artist and the British Film Institute

Prospect Cottage became his Eden and later became something of a shrine to the artist since his death. It faced a turbulent future and at risk of being bought by a private company after his partner Keith Collins passed away in 2018. Until 31st March 2020, Art Fund ran a campaign to save the building as an archive of his work and a site of pilgrimage for many around the world.