“I don’t fight for anything but I stand for many things, one of them is art. Art has the ability to: heal; transcend culture, age and language; change the way we see the world and; educate.”

– Tony Albert

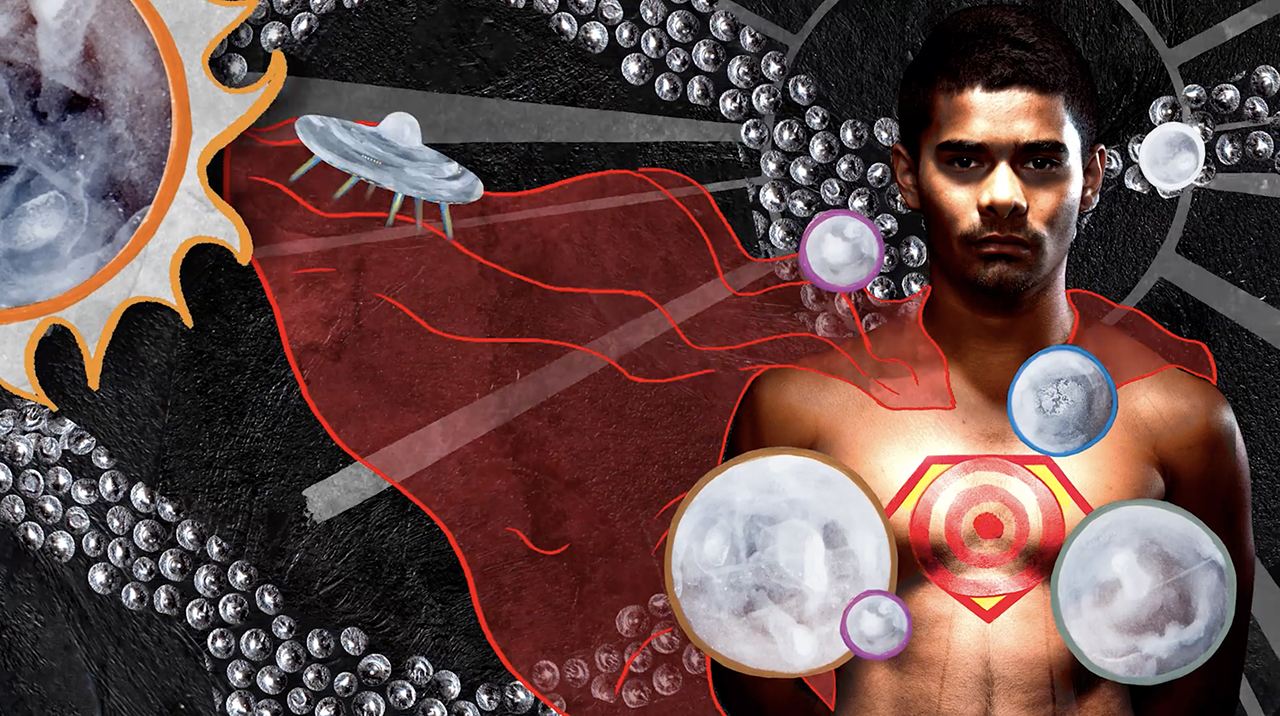

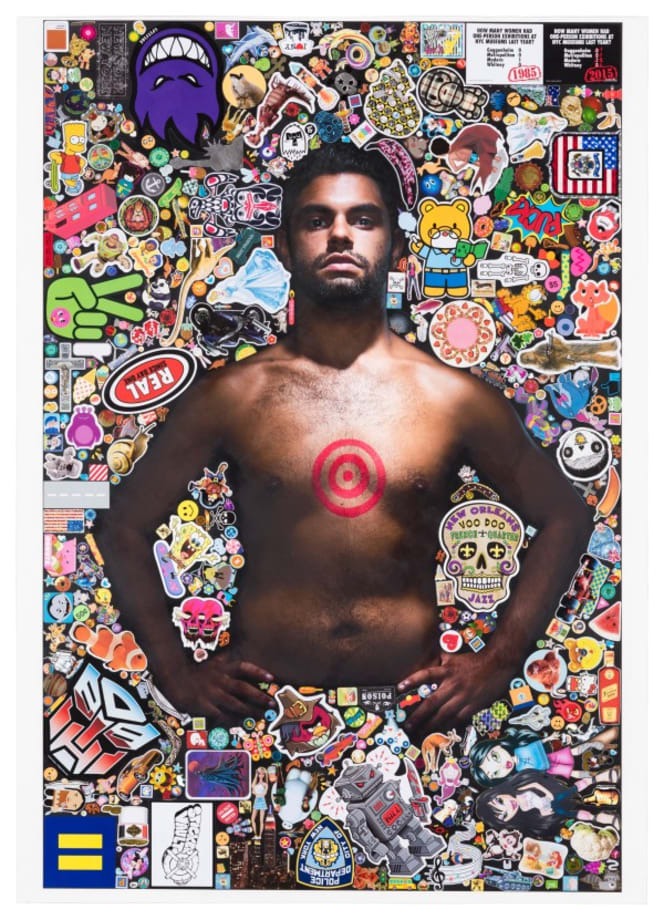

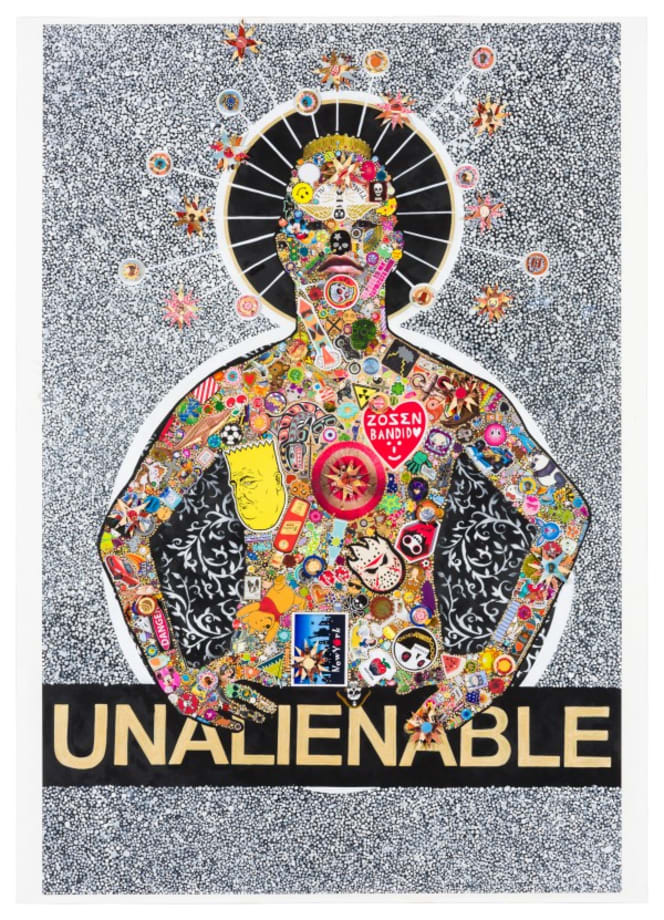

Tony Albert, “I Am Visible”, 2019 | Image courtesy of the artist, Sullivan+Strumpf and Sunpride Foundation

Born in 1981 in Townsville, North Queensland, Australia, Tony Albert is a Sydney-based artist working a wide range of mediums including painting, photography and mixed media. His work engages with political, historical and cultural Aboriginal and Australian history, examining the legacy of racial and cultural misrepresentation and seeking to rewrite historical mistruths and injustice.

Tony Albert with his work “The Hand You’re Dealt”, 2015 | Image courtesy of Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, University of South Australia

Albert’s interest in art was from a very early age, spending one day a week at a special art college. He often feels like a bit of an outsider on the history of art, but what he knows about is his life, the life of his family and the life of his community.During high school, Albert was inspired to be an artist after discovering the work ofcontemporary Aboriginal artists such as Gordon Bennett and Tracey Moffatt, offering him a sense of belonging, courage and fearlessness inspiring. In 2004, Albertgraduated from the Queensland College of Art, Griffith University, Brisbane, with a degree in Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art. He is also one of the members of ProppaNOW, the art collective for Indigenous Australian artists in Queensland,aiming to counter cultural stereotypes and give a voice to urban artists.

Left to right) Members of ProppaNOW: Tony Albert, Jennifer Herd, Gordon Hookey, Megan Cope, Richard Bell and Vernon Ah Kee | Image courtesy of Rhett Hammerton and The University of Queenland Art Museum

Albert realized that creating work is not only visually appealing, but also acts as a vehicle for stimulating discussion and creating change. His artistic practice involves collaborating, repurposing and re-imagining popular culture paraphernalia, social and political movements, in order to tell the stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

His fascination with kitsch “Aboriginalia”

“Aboriginalia” is a term coined by Albert to describe the kitschy paraphernalia that depicts stereotypical Aboriginality from a colonial ethnographic perspective. During his childhood living in the suburbs, he started collecting “Aboriginalia”, the aboriginal kitsch objects filled tourist shops to depict cringey stereotypes of Indigenous people, including playing cards, tea towels, ashtrays, wall-hangings and mugs. The collection of “Aboriginalia” initially stemmed from something very innocent. Albert genuinely loved the iconography and imagery, particularly the faces, which reminded him of his family. After studying history in high school, Albert became more aware of Indigenous issues. He now understands their deeper connotations – how they co-opt and disempower Indigenous voices.

Tony Albert’s first major solo exhibition entitled “Visible” at the Queensland Art Gallery in 2018| Image courtesy of the artist and the Queensland Art Gallery

At the age of 37, his private collection of these objects was shown in his first institutional survey exhibition at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art. These objects combined in an installation, highlighting the absence of Aboriginal people in mainstream Australian narratives, and to cross-examine notions of difference.

The (in)visibility and optimism in the face of adversity

Optimism is Albert’s underlying philosophy in life, realizing the cycle of racism is ever present and the history is uncomfortable. His work shows individualism and reframes his chosen subject in a way that is true to his lived experience and the experiences of those around him. Through his art, Albert asks the audience to remember the history, and to guard against its repetition, offering a way forward and breaking the cycle.

Installation view of “I am Visible” in Enlighten Festival 2019 at National Gallery of Australia, Canberra | Image courtesy of the artist and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

“I am Visible”, projected across the 50m-high facade are images of young Aboriginal men, shown with targets on their chest, intertwined with musical lyrics and words from Indigenous languages, is one of Albert’s recent work in Enlighten Festival 2019 at National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. The visual elements of “I am Visible” represent the visibility, and in turn invisibility, of Aboriginal people, leading audience to bear witness to the realities of racial profiling and miscarriages of justice in contemporary Australian society. Many images in the projection are woven from Albert’s practice of the last five years, particularly his Brothers series, including “Brothers (New York Dreaming)” and “Brothers (Unalienable)”.

Tony Albert, “Brothers (New York Dreaming)”, 2016 | Image courtesy of the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf

During his residency at Artspace in Sydney in 2012, Albert met a tragedy within the local community. After a shooting in Kings Cross, young boys who took their shirts off and drew targets all over their bodies were at the protest at Government House, expressing their views on police violence and brutality. The spectacle affected Albert to work with the Kirinari Hostel, a Sydney youth hostel for Aboriginal boys and men, to produce the Brothers series in 2013.

Tony Albert, “Brothers (Unalienable)”, 2016 | Image courtesy of the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf

Photographic portraits show a number of young Aboriginal men from the hostel with targets painted on their chests. The boys stand resolute and proud of who they are and their culture. The target is a symbolic role with various connotations. It could be interpreted as Aboriginal art, a speaker with the vibrations of sound waves or a rock thrown into a pond and the ripple effect that comes out of it. Albert also taps into the use of social media, popular culture and familiar objects such as superheroes to connect with; give power to and inject love and appreciation into people who feel forgotten by the rest of Australia, encouraging Aboriginal people to insert themselves into the picture.