“I think dreams are really important as a means of escape, and to discover a new reality. It’s a way for us to process information. It’s similar to the way we need movies – the need to be in the dark and to lose oneself.” — Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Apichatpong Weerasethakul | Image courtesy of the artist, Harit Srikhao and The New Yorker

Born in 1970 in Bangkok, Apichatpong Weerasethakul grew up in Khon Kaen in north-eastern Thailand. He is a Thai independent film director, screenwriter, and film producer. His unique cinematic style was already manifest in his early work, which fused the documentary with the fictional, the journalistic with the folkloric, the ghostly with the sci-fi, sensitively responding to political and social issues through a non-linear, mismatched narrative. The themes reflected in his body of work include dreams, nature, sexuality and the people of his native Thailand.

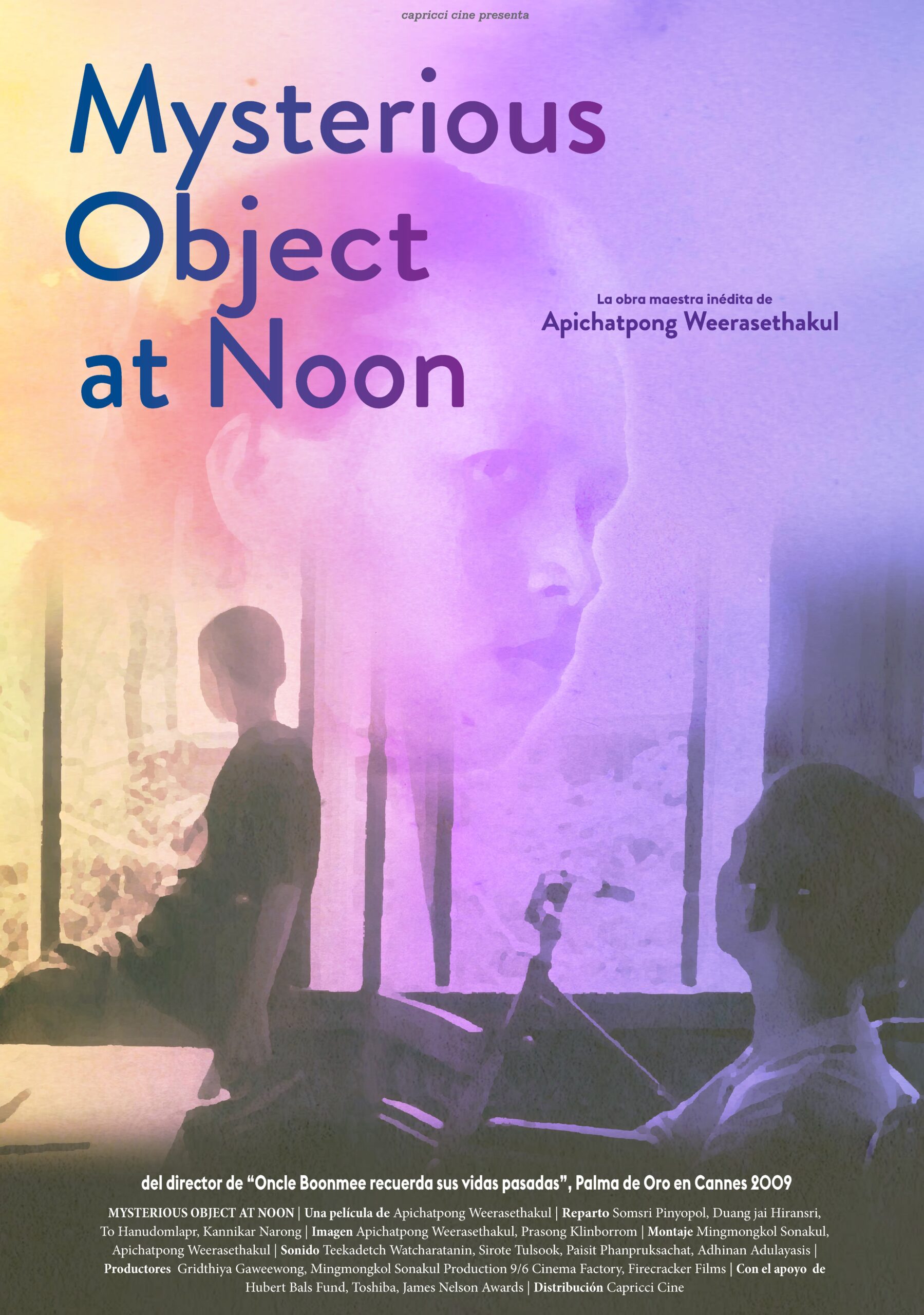

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Mysterious Object at Noon, 2000 | Image courtesy of the artist

After obtaining a bachelor’s degree in architecture at Khon Kaen University in 1994, Weerasethakul started making films and videos and became an independent film producer in Thailand. In 1997, he graduated from Master of Fine Arts in filmmakingat the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1999, Weerasethakul started his own production company Kick the Machine to support and promote independent productions and experimental films made in Thailand as well as strives for Thai filmmaker’s creative distribution and screening rights. In the following year, he made his first feature film Mysterious Object at Noon (2000).

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, 2010, Film still | Image courtesy of the artist

His artworks are collected by Tate, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Centre Pompidou, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, M+, and others. Significant exhibitions include Primitive, New Museum, New York (2011); For Tomorrow ForTonight, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing (2011); and The Serenity of Madness, Taipei Fine Arts Museum (2019). Almost all of his features have gone on to garner prestigious award nominations and wins, including the Cannes Film Festival Prix de Jury for Tropical Malady (2004) and the Palme d’Or for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), the first Southeast Asian film that ever received such honour.

Light and Memory

Weerasethakul’s work is his personal reaction to a particular situation or place, not a documentation or historical record. For him, light – both as medium and as metaphor – is a potent force which is a power to reveal and to conceal. “When telling the stories, I always think of Plato’s The Allegory of the Cave. The self-identity that is shaped is related to the information received in our growing process. In the Plato’s theory, we can see how the people in the cave perceive the world only through their own shadows... People can only receive those limited information after being filtered.And once other information comes to our life like sunlight in the theory of the Cave,the initial reaction is not to believe in its authenticity. This question into the authenticity is one of the main themes of these works.”

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Power Boy (Close Up), 2011 | Image courtesy of the artist

Fireworks (Archives) (2014) is Weerasethakul’s offer to his home region, shot in the sculpture park of a little-known nonconformist temple in the northeast of Thailand. The work attempts to shine light on parts of our memory shut away deep within, banished by our conscious minds. It explores the relationship between memory and light, alluding to a recent scientific report that shining light on particular cell groups within the brain would bring back specific memories.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Fireworks (Archives), 2014 | Image courtesy of the artist and SCAI The Bathhouse

“Fireworks (Archives) functions as a hallucinatory memory machine. It catalogs the animal sculptures at a temple in a northeast where I grew up. To me, the region’s arid land and political force from Bangkok drove people to dream beyond the everyday’s reality. The oppression had led to several revolts in the region, and the temple’s wayward statues are one such revolt. Here my regular actors blend in with the illuminated beasts at night. Together they commemorate the land’s destruction and liberation.”

Dream and Memory

“I’ve always associated dreaming with watching movies. I think the structure of dreams is quite similar to that of movies… Dreams are like everyone’s own movies. I was inspired not only by my stories with the people around me, but also by the ‘movies’ that happened in my head at night. To me, these works are almost like a kind of diary, and the characteristic of a diary is truthfulness. Dreams are not usually considered real, but for me they are because I myself witnessed everything in my head when they happened.”

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, The Vapor of Melancholy, 2014 | Image courtesy of the artist and Sunpride Foundation

Weerasethakul’s body of work, including Teem (2007), HaiKu (2009), Cemetery of Splendour (2015) and Fever Room (2018), unveils variations on the themes of dreams and sleeping that he has experimented with, making references to history, folklore, and memories from his home region in northeast Thailand.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Teem (2007), Exhibition view of The Serenity of Madness, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2019 | Image courtesy of the artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum

“Well, my boyfriend (Teem) likes to sleep, so I thought, ‘Let’s shoot this.’ It’s a game to see if the presence of the camera has some kind of energy to wake him up. But it goes back a long time in my work. Even in Dilbar, you see images of the construction workers sleeping. I think dreams are really important as a means of escape, and to discover a new reality. It’s a way for us to process information. It’s similar to the way we need movies – the need to be in the dark and to lose oneself.”