“Going inside my paintings helped me calm my mind… The working ethos of the studio is first and foremost: how do we create beauty?… The troubles of the outside world simply don’t exist within this bubble, and I really do believe aesthetics have a healing quality that can make us feel better about ourselves.” — Raqib Shaw

Raqib Shaw | Image courtesy of the artist, Andrew Hinderaker and The Wall Street Journal

Raqib Shaw (b. 1974, Calcutta, India) is known for his opulent and intricately detailed paintings of imagined paradises, often with surfaces inlaid with vibrantly colored jewels and painted in enamel. Shaw’s paintings and sculptures evoke the work of Old Masters such as Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) and Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), whilst drawing on multifarious sources, from mythology and religion to poetry, literature, art history, textiles and decorative arts from both eastern and western traditions, all infused with his imagination.

Born in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) to a family of merchants, grew up in Kashmir and later lived in New Delhi, Shaw travelled to London in the early 1990s. Holbein’s work The Ambassadors (1533) in the National Gallery significantly enhanced his understanding of symbolism and narrative in painting. In the late 1990s, Shaw moved to London and completed his BA and MA at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in 2001 and 2002 respectively. Soon after graduation, his paintings and exhibitions were met with widespread acclaim. Shaw has had solo exhibitions at Tate Britain, London (2006); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2008); Manchester Art Gallery (2013); Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague (2013); the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (2018) and among others.

Impacted by family business and Old Master painters

Shaw’s body of work reveals an eclectic fusion of influences—from Persian carpets and Northern Renaissance painting to industrial materials and Japanese lacquerware—and are often developed in series from literary, art historical, and mystical sources. He not only references the artistic traditions of Persian and Mughal miniature painting but also draws from the artistic lexicon of Old Master painters including Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), John Constable (1776-1837), Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) and Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569).

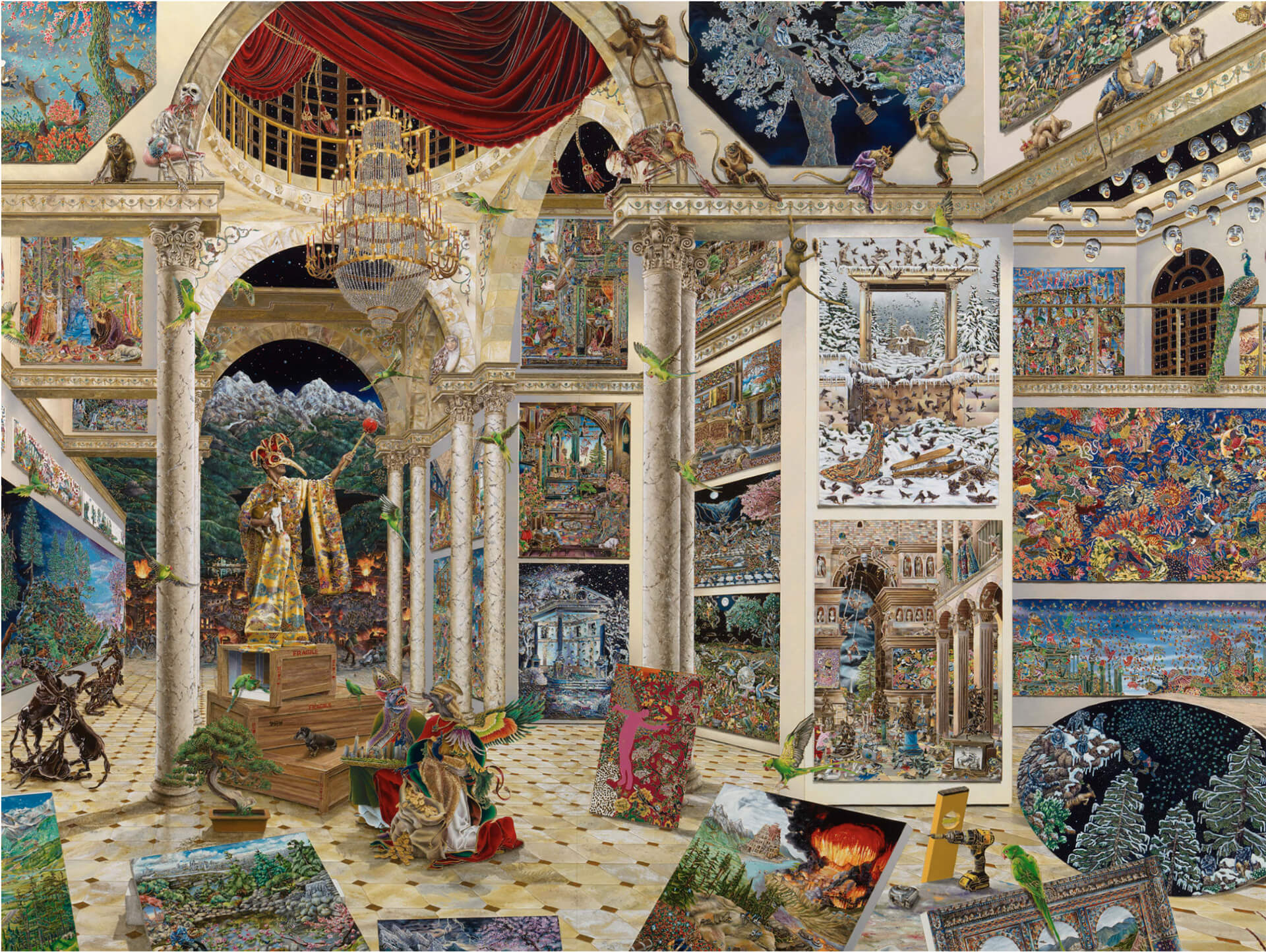

Raqib Shaw, The Retrospective 2002-2015, 2015-2022 | Image courtesy of the artist and White Cube

“My work exists on two levels, in the relationship between the background and the foreground and how they talk to each other. It’s also a satire on human society and the human condition in general.” From 1992 to 1998, Shaw worked for his uncle in the family business, ranging from interior design, architecture, jewellery to antiques and carpets, brought him to get closer to the beautiful things that were being made in India. During his studies in London, he experimented with several materials such as enamel, household and car paint, bought from a local branch of Leyland, were to set the foundation for his technique of manipulating pools of industrial paint with a porcupine quill.

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors,1533 | Image courtesy of The National Gallery

Family business also brought him to London and met Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors (1533) that prompted him to become an artist. “What I really loved about The Ambassadors was that it was a painting about merchants. And I thought to myself, I don’t want to be the merchant, I want to be the guy who paints merchants. Merchants are not fascinating; people who paint merchants are far more fascinating.”

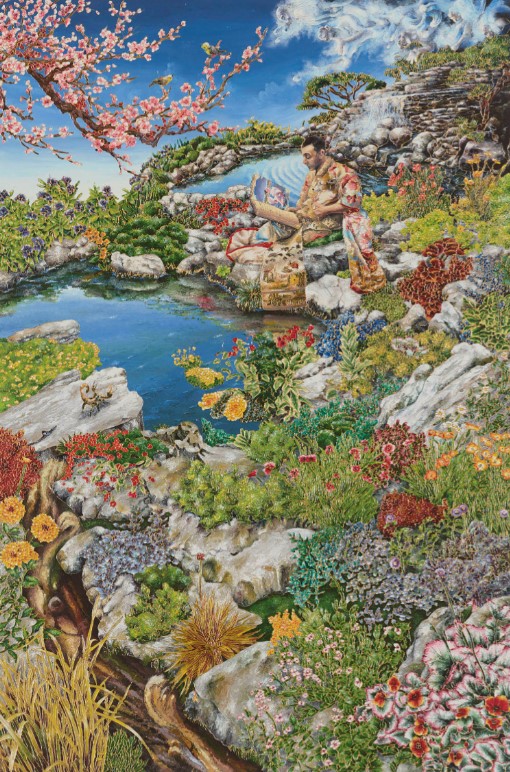

Shaw’s world in miniature on canvas

Shaw’s paintings reflect and engage with nature, high-altitude flora and fauna within his studio garden to create “a world in miniature that could be magnified on canvas”. Shaw has survived fire, cancer and civil war in his life. Kashmir, where his mother’s garden was and a place that he grew up, is described and considered as “Garden of the Himalayas” and “Paradise on Earth”, now a no-man’s-land fought over by India and Pakistan. Civil war and political unrest drove him to New Delhi in 1992, turning his love for his lost homeland of Kashmir into mind-blowing fantastical works.

Raqib Shaw, La Tempesta (after Giorgione), 2019-2020 | Image courtesy of the artist and White Cube

In 2011, Shaw moved into an old factory in Peckham, south London, converting it into a home, studio and multistorey garden that he rarely leaves. The garden is Shaw’s multiple topographies, landscapes, histories and life experiences collide.

Raqib Shaw in his studio garden, Peckham, London | Image courtesy of the artist, Elephant.art and Louise Benson

“I’ve been in this concrete studio situation for 19 years. But post-cancer, I realised I wanted each and every frame to be beautiful and healing. Don’t you think this place is calm? And have you noticed something? Time doesn’t exist here. I don’t wear a watch. I don’t do time.”

Raqib Shaw, Sirens of Mirth in the Garden of Perpetual Pleasure, 2020-2021 | Image courtesy of the artist and Sunpride Foundation

Inspired by Dutch artist Hieronymous Bosch, Shaw wants to create a wildly imaginative vision of worldly pleasures through his series of The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Raqib Shaw, The Garden of Earthly Delights X, 2004 | Image courtesy of the artist

“I wanted to do my own Garden of Earthly Delights, a garden that would be incredibly autobiographical, and highly coded, but also a garden that would enable me to share my sensibility to the rest of the world… Every single body that you see in this painting is based on my own body, the only body that is not my body is the body of the king. This is the guy with a toucan beak. And that is the body of the gay porn star Jeff Stryker. So that’s the way this painting was made from an emotional point of view.”