“Art is the ability to turn one’s gaze to the world of oblivion. This is the way in which I understand art at fundamental level. The value of art is its ability to look into the world of oblivion and to find things that are generally unrecognized, forgotten, invisible and impossible to tell.” — Yasumasa Morimura

Yasumasa Morimura | Image courtesy of the artist and Stir World

Yasumasa Morimura (born 1951, Osaka, Japan) is a conceptual photographer and filmmaker whose work deals with issues of cultural and sexual appropriation. He uses extensive props, costumes, makeup, and digital manipulation to create and insert his images into portraits of historical artists and celebrities, resulting in often-uncanny recreations of iconic works.

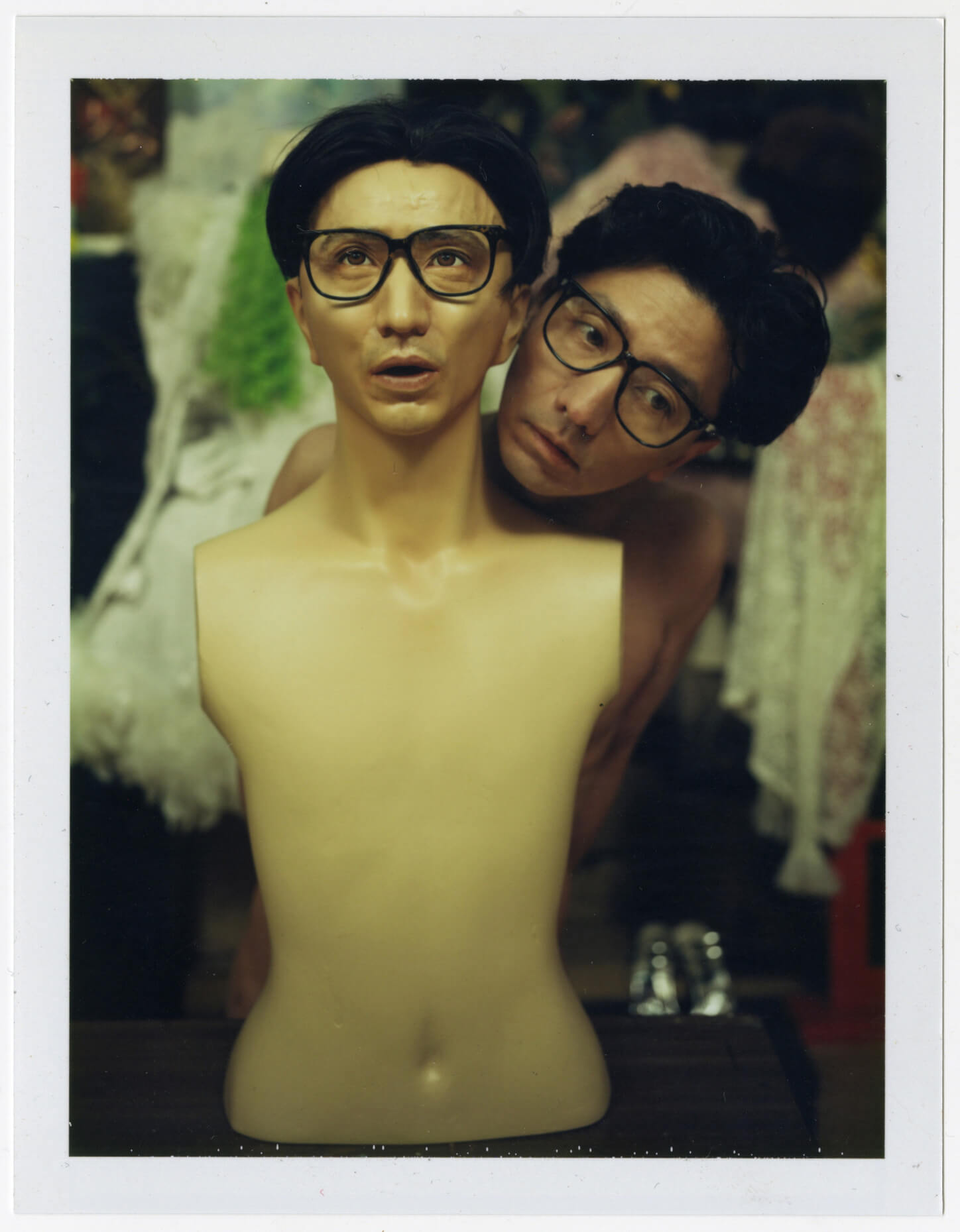

Yasumasa Morimura, “Portrait (Futago)”, 1998 | Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine

Morimura’s signature works include Art History series, Actress series, and A Requiem series. His reinvention of iconic photographs and art historical masterpieces challenges the associations the viewer has with the subjects, while also commenting on Japan’s complex absorption of Western culture. Through his depiction of female stars and characters, Morimura subverts the concept of the male gaze. Within each image he both challenges the authority of identity and overturns the traditional scope of self-portraiture.

Yasumasa Morimura, “An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo (Hand Shaped Earring)”, 2001 | Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine

Morimura has had solo exhibitions in Japan, including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, the Yokohama Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Photography in Tokyo. His work has been collected by numerous prominent public and private collections, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and amongst others. Morimura@Museum have been established in 2018, where visitors can view Morimura’s documents and self-produced exhibitions.

Self-portraits of Morimura

“I was trying to leap across binaries of categorization—masculine and feminine, East and West—as well as ideas such as the feminization of the East, Asia becoming synonymous with woman, the feminine mystique. I began playing around with tropes of what is perceived as sexy and exotic to the West.”

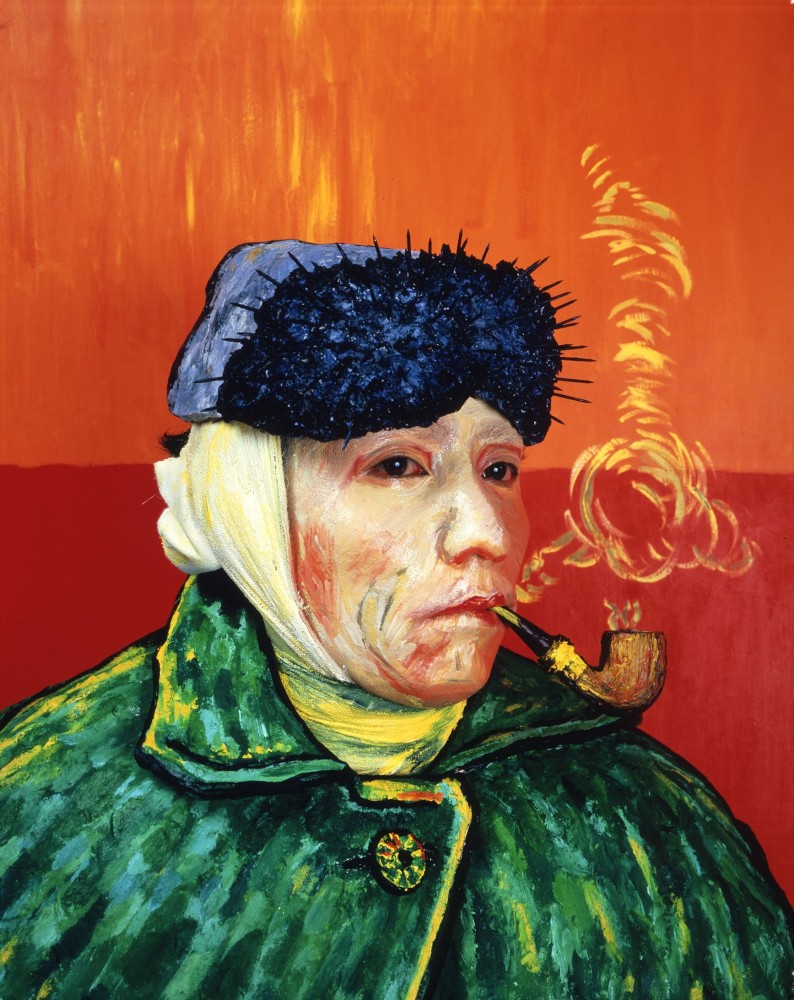

Yasumasa Morimura, “Portrait (Van Gogh)”, 1985 | Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine

In 1985, Morimura started marking self-portraits by using prosthetics, cosmetics, and sets to assume the roles of figures who signify more than themselves, including old masters’ paintings, Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Édouard Manet’s Olympia, Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe, and Michael Jackson.

Yasumasa Morimura, “One Hundred M’s self-portraits”, 1993-2000 | Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine

When he stands in front of a classical portrait painting, there is always a sense that the painting is a mirror, gradually starting to feel that the depicted figure is a self-portrait of himself, the very person looking at the painting. It is as if they are not separate entities, but the mirror image of one another. This intimate relationship is extremely stimulating for him.

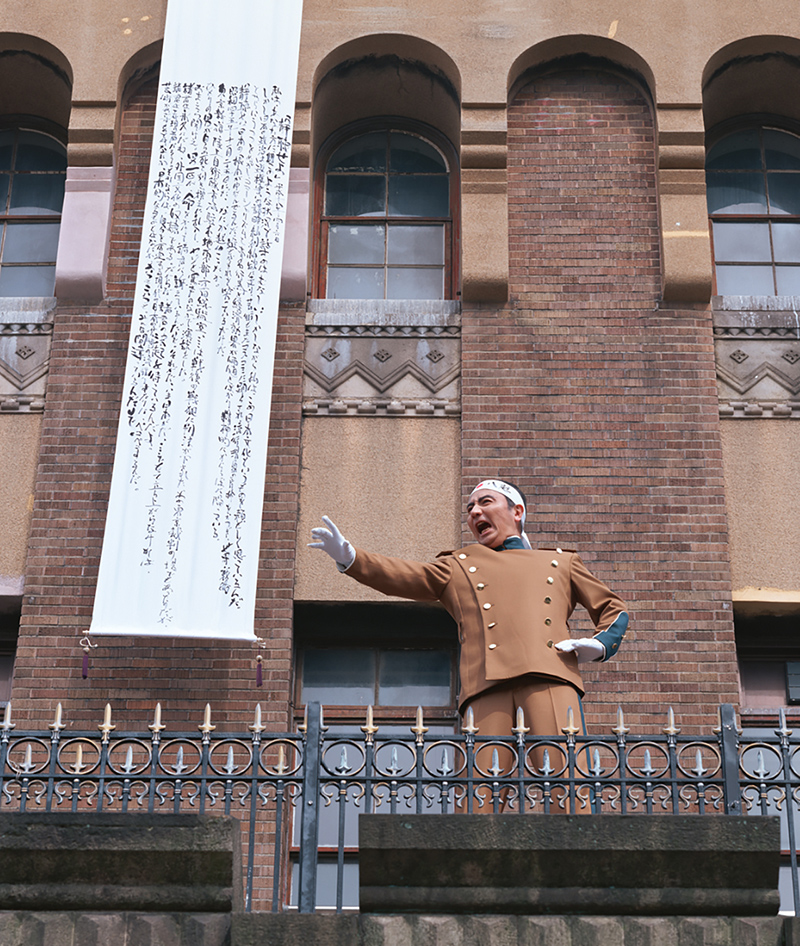

An homage to Yukio Mishima in the series of A Requiem

One of the historical personages whom Morimura has repeatedly transformed himself into is author Yukio Mishima (1925-1970), who collaborated, as a model, with the photographer Eikoh Hosoe on the erotically charged and art historically allusive photobook of 1963, Barakei (“Ordeal by Roses”). Among the most iconic images of postwar Japan is a photograph of Mishima delivering a speech from the balcony at Ichigaya Camp, the Tokyo headquarters of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. “I have always been interested in him. One thing that connected the two of us is the Self-Defense Forces. After I graduated from college, I got a job and was supposed to participate in training seminars organized with the SDF [a common practice at a traditional Japanese company]. I couldn’t stand the idea, so I quit the company after only three days. I wasn’t proud of it – in fact, it nagged me for a long time. Many years later [in 1995], I finally went to the SDF when I was making a work based on a scene from the movie Casablanca, for the Actress series. I showed up there as Ingrid Bergman, and the officers were so kind, so happy to help me. I could go there and leave there with dignity, as a woman. Yukio Mishima went to the SDF headquarters as a man, to launch a coup. When I was leaving, I thought, Mishima couldn’t get out; he died there.”

Morimura Yasumasa, “A Requiem: Mishima, 1970”,

2006 | Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine

“Seasons of Passion / A Requiem: Mishima” (2006) is an homage to Yukio Mishima, who lived through an era of postwar Japan’s spiritual history in which there was a division between things considered Japanese and those considered Western. Meanwhile, the work seeks a way to bring an element of Mishima, and his struggle to confront that divided history into the 21st century.

(Left) Morimura Yasumasa, “Seasons of Passion / A Requiem: Mishima”, 2006 (Still from HDTV, 7 minutes 47 seconds) | Image courtesy of the artist and Sunpride Foundation

(Right) Mishima Yukio on the Ichigaya Self-Defense Forces Headquarters balcony, 25th November1970 | Image courtesy of Trans-Asia Photography Review Images

“That was when I was 19, November 25, 1970, the Japanese author Yukio Mishima attempted a coup and committed seppuku (ritual suicide). I’ve been thinking about what it means throughout my career. 19-year-old me was tremendously pushed by Mishima. But now, I am looking at the Mishima incident more calmly, more objectively. The incident was very tragic, but I think the incident includes a variety of elements, both tragic and comedic. What I was trying to do is probably to superimpose both art expression and art critique. To critique is to use words. To use these words to narrate, and also to express my art – an amalgamation of the two – that’s the art expression I’m working on right now.”